Creating a Shared Identity as Singaporeans

Forging the Singapore Identity

Our national identity is constantly evolving with the country’s changing demographics, generational shifts, and renewed mindsets about our values and aspirations.

The make-up of our population has changed significantly in recent decades, driven by an ageing population, shrinking birth rates and immigration policy changes. All these factors have, in turn, profoundly influenced the way Singaporeans view themselves as citizens of this nation they call home.

The evolving dialogue on our shared values and identity

Singapore’s common values transcend race, language or religion. How these values are articulated and expressed through our Singapore identity has evolved, even as the country held steadfast to the national pledge to be “one united people” regardless of background since its independence.

Efforts to consciously shape a national identity have shifted from a top-down approach to a more collaborative one.

In 1988, former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong proposed the idea of a national ideology to help Singaporeans preserve their Asian values amid growing exposure to western lifestyles and ideologies.

A committee led by the then Minister for Trade and Industry Lee Hsien Loong was convened to advance a debate on national ideology, and key values common to the various races and communities in Singapore were identified. The findings were published as a White Paper on 2 Jan 1991, before being debated in Parliament, and eventually adopted on 15 Jan 1991.

Amid concerns that Singaporeans were too preoccupied with the materialistic “5 C’s” values - Cash, Car, Credit Card, Condo and Country Club – in the post-Independence years, the “Remaking Singapore 2002” White Paper sought to relook broad social policy. It steered attention towards the aspirations of a third generation of citizens for a more multi-dimensional, inclusive future for Singapore.

While the refreshed identity had an appealing message, it was still seen as a relatively top-down exercise with input from Singapore’s political, academic and professional elites, as it did not get general feedback from the “man on the street”.

To address this groundswell of public sentiment about the need for wider engagement, the Government launched an initiative in 2012, known as the “Our Singapore Conversation”, to interact with Singaporeans on an unprecedented scale: over 47,000 Singaporeans participated in more than 660 dialogue sessions – both online and in-person or through surveys – over one year to articulate their views and aspirations.

Through these sessions, citizens were invited to share their views on three questions: What matters to us? What are the values we hold? How can we work together to meet the challenges of the future?

From these conversations, five core aspirations citizens felt should guide Singaporean society emerged: opportunities, purpose, assurance, spirit and trust.

Singaporeans desired opportunities to make a good living and realise their potential, regardless of their background. They wanted to live with purpose as individuals, community members, and Singaporeans. They also wanted assurance that basic needs such as housing, healthcare and public transport are affordable and within reach. Singaporeans aspired to a strong “kampong spirit” and society anchored in our shared values while contributing to building a common future founded on trust among Singaporeans and between the Government and citizens.

The Singapore Conversation continues today, as the Government engages Singaporeans and uses more varied formats such as social media and mobile apps to conduct broad-based discussions and gather feedback about pertinent issues.

Creating a Shared Identity as Singaporeans

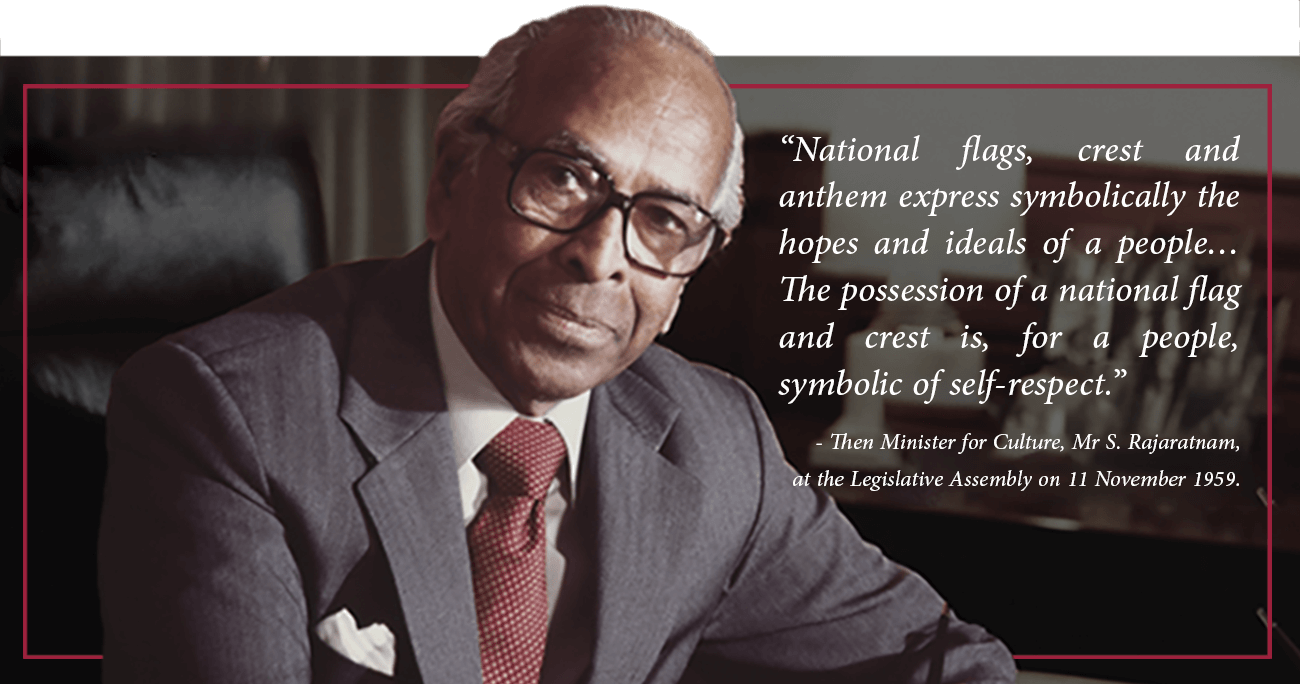

For former Deputy Prime Minister Dr Toh Chin Chye, the national flag, crest and anthem were more than just symbols for a newly independent Singapore.

Amidst the communal tensions and racial riots of the 1950s and 60s, Singapore needed to forge a common identity and sense of belonging among its people. These symbols would help forge a sense of unity, shared purpose and, over time, a common destiny towards which all Singaporeans could strive. However, unlike other nations which had a much longer history to draw upon to build a shared identity, Singapore did not have that luxury.

The national anthem was the first symbol to be created. “Majulah Singapura” (Onward Singapore) was composed in 1958 by Singapore composer Zubir Said. It was originally commissioned by the City Council of Singapore in 1958 as an official song for the council’s function.

After Singapore achieved self-governance in 1959, a shorter and more upbeat version was made into our national anthem. Majulah Singapura is a musical expression of Singapore’s identity as a nation, and its melody and lyrics echo the enduring hope and spirit of Singaporeans for progress. It also speaks to Singaporeans coming together to work towards a common goal – a better future.

According to Dr Toh, Majulah Singapura was chosen for its patriotic lyrics that expressed the aspirations of the people of Singapore. He added that the lyrics of the national anthem should be in Malay as it is “the indigenous language of the region, as English is not native to this part of the world (…) (the) Malay version of the national anthem would appeal to all races (…) it can be easily understood. And at the same time can be easily remembered (…) it must be brief, to the point; (…) and can be sung.”

Thereafter, our national flag was unveiled on 3 Dec 1959. “The political purpose was to have a flag around which the three different communities of Singapore can rally around. That is important,” said Dr Toh, in an interview with the National Archives of Singapore on 23 August 1989. He was tasked to create the symbols back in 1959 when Singapore achieved self-governance. (Listen to the rest of his interview here.)

He studied the flags of other countries with the intention of creating something unique to Singapore. He eventually settled on the red and white design, with the use of five stars to represent the values of democracy, peace, progress, equality and justice.

Red was chosen because it symbolised prosperity and happiness, while white – formed when all seven colours of the rainbow are combined – was chosen to symbolise the unity of the different races. The crescent moon, which represents Singapore as a new nation, was added later because Dr Toh wanted to “remove any apprehension that we were building a Chinese state”. After all, “there are also five stars on the flag of the People’s Republic of China”, he said.

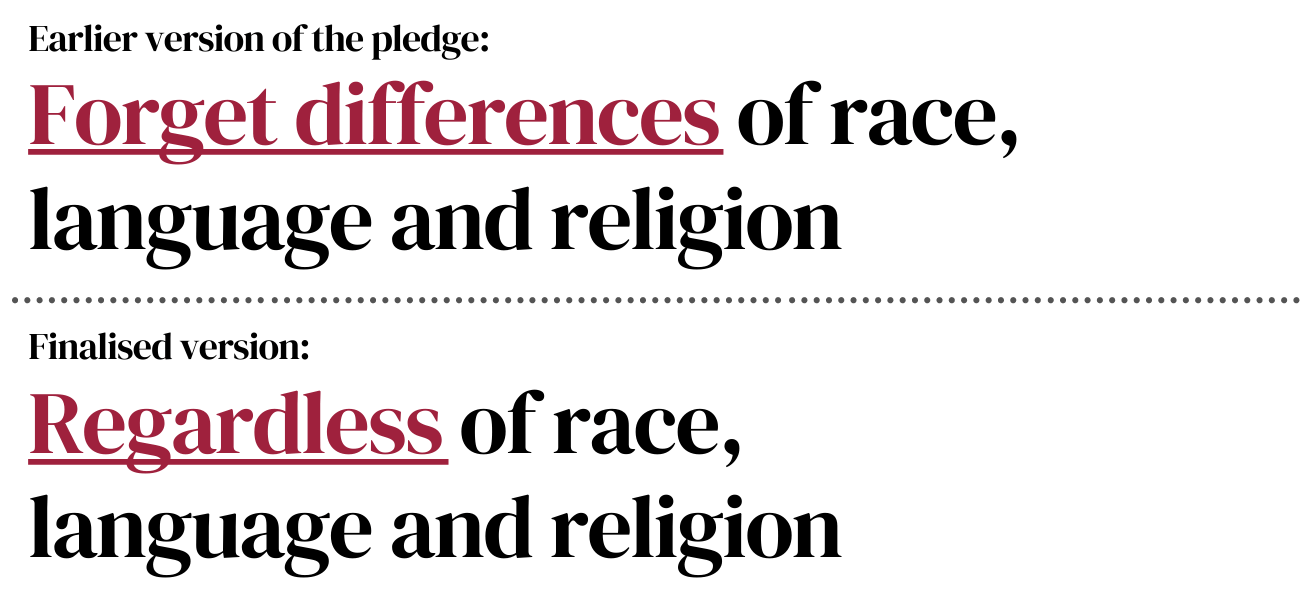

The idea of a pledge was also mooted as a way to inculcate national consciousness and patriotism in schools. Then-Minister for Foreign Affairs S. Rajaratnam, who authored the pledge, believed that differences in language, race and religion were potentially divisive. Hence, he made use of the pledge to emphasise that these differences could be overcome if Singaporeans were united in their commitment to the country.

The fundamentals of Singapore’s multicultural society were not to forget or paper over differences, but to acknowledge them, set them aside, and go beyond them – regardless of race, language or religion.

After three drafts and multiple revisions, the Singapore pledge was eventually finalised. On 24 August 1966, about 500,000 students at all 529 government and government-aided schools took part in the first daily recitation of the pledge before the national flag.

(Images: National Archive of Singapore)

(Images: National Archive of Singapore)

Singaporeans have increasingly sought to use the flag and other national symbols to show their national pride and solidarity in ways not anticipated by the 1959 rules. On 13 September 2022, four more national symbols – our national pledge, national flower Vanda Miss Joaquim, lion head, and public seal – have been formally recognised under the new National Symbols Bill.

Forging a National Identity

While symbols may help Singaporeans identify with the country, it did not create our national identity overnight. Forging a national identity required time and a conscious effort to allow people opportunities to interact and form bonds with one other. They also need to feel that they have a tangible stake in the country’s development and progress.

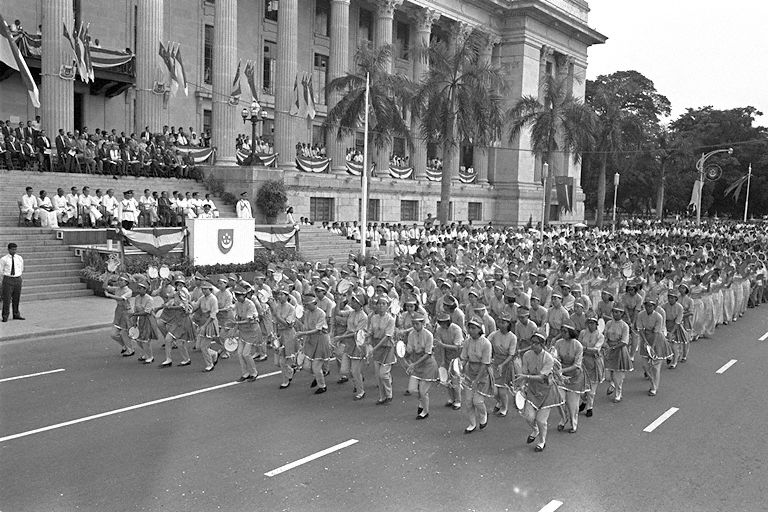

(Images: National Archives of Singapore)

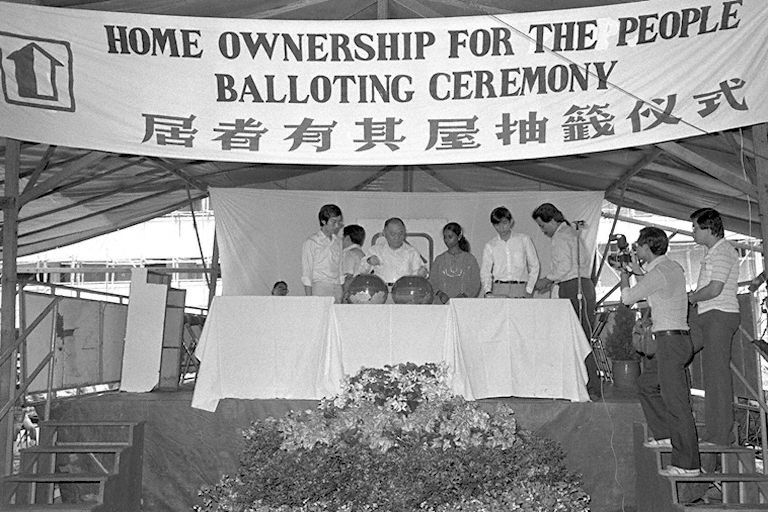

(Images: National Archives of Singapore)

One of the ways this was done was through the housing scheme introduced to encourage home ownership among Singaporeans. In February 1964, the government introduced the Home Ownership for the People Scheme to give citizens a tangible asset in the country and a stake in nation-building. Today, about 80% of the population live in Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats, and a vast majority own their flats.

A big part of forging a common identity lies in the intangible aspects of culture that people share. For example, the experience of growing up in Singapore is a unique one that shapes shared experiences that Singaporeans can relate to.

Apart from that, art and music were also used to help create a Singaporean culture in the 1990s. Led by then-Acting Minister for the Arts George Yeo, Singapore built The Esplanade and new museums, as well as set up the National Arts Council (NAC).

Over the years, we have developed a distinctly Singaporean cultural experience, drawing from our richness and diversity from our roots as a migrant nation. Many aspects of our culture are a rich amalgamation and hybrid of Chinese, Malay, Indian, European cultures and so on. Our hawker culture, for one, has made it onto UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

![]()

Another example of what is uniquely Singaporean is the evolution and use of Singlish, an English-based creole which was formed after prolonged linguistic contact between people of different communities and cultures in Singapore.

Singlish grammar mirrors that of Malay, by doing away with most prepositions, verb conjugations, and plural words, while its vocabulary reflects the broad range of the country’s immigrant roots. It borrows from Malay, Hokkien, Cantonese, Mandarin and other Chinese languages, as well as Tamil from southern India.

A national identity acts as a bulwark against forces that may seek to fracture society. It pulls Singaporeans together in a time of crisis instead of fragmenting into separate ethnic groups.

This was the concern that then-PM Goh Chok Tong brought up during a parliamentary debate on 5 May 1999. He said, “in a crunch, where the interests of the tribe and the state diverge, can we be sure that the sense of belonging to a state will be stronger than the primordial instinct of belonging to a tribe?”

Standing in Solidarity

And indeed, there are many times when we have stood together as a nation in solidarity, from moments of grief, to moments of pride.

On 23 March 2015, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, passed away. Over a week, hundreds of thousands paid their last respects at the Istana and 18 community tribute centres across the island. Queues snaked as people braving the blazing sun for eight hours or more at times to say their last goodbyes. Singaporeans took care of one other as they waited to pay their respects, handing out paper fans, food and drinks paid for from their own pockets. In grief, Singaporeans showed solidarity.

Apart from that, at the 2015 Southeast Asian (SEA) Games, Team Singapore swimmers won the women’s 4x200m freestyle relay. The national anthem played while they stood on the podium. However, the PA system crackled and died midway through. Undeterred, Singaporeans in the stands picked up the anthem from where the PA system left off, singing even louder, till the end of the national anthem. The heartfelt rendition drew loud applause from the packed arena, with the swimmers visibly moved.

These experiences are examples of the closeness and solidarity that stems from Singaporeans seeing ourselves as one, instead of separate groups. In his 2019 National Day Rally speech, PM Lee highlighted the importance of developing a common national consciousness. He said that it has taken many years but the concept of being Singaporean is now firmly etched in all Singaporeans.

Now, as the world enters troubled times, Singapore faces new and daunting challenges that we can only face if we stand together as a nation.

Finding a Shared Identity with a New Social Mix

As a global city and international business hub, just like how we were a migrant nation, we continue to attract people of all nationalities and cultures here. This has led to a gradual change in our social mix over the years. In addition to the existing multiracial, multi-religious and multicultural local population, the social fabric now also includes new citizens and foreigners who bring with them different cultures, beliefs and practices.

Integrating new citizens and permanent residents

In 2020, Singapore saw about 27,470 new permanent residents and 21,085 new citizens, according to the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority. These figures are lower than previous years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which were likely due to travel restrictions and operational issues arising from COVID-19.

While some newcomers have successfully built strong ties with the community, others are perceived to stay in their own circles instead of making substantial efforts to learn and appreciate Singapore’s multicultural norms.

This may be why only 17 per cent of Singaporean youth feel that locals and foreigners get along well here despite their differences, compared to 38 percent of foreigners, based on a recent poll by the National Youth Council (NYC) in 2022.

PM Lee noted in his National Day Rally speech in 2019 that just like Singapore’s forefathers, the immigrants of today have to similarly undergo the process of gradually identifying themselves as Singaporeans, and becoming Singapore citizens. This is a process that took many decades. Singapore’s forefathers arrived as sojourners. Those from China intended to return to their homeland one day, but in the end, the majority chose to remain. They saw this as their new home, and worked to make it succeed, and defended their nation fiercely. Gradually, a Chinese Singaporean identity was developed.

It was the same for Malay and Indian Singaporeans. During the period of anti-colonial struggle, the Indians were inspired by India’s own struggle for independence while the Malays were inspired by the nationalist movements in Indonesia and Malaya. But like the Chinese, they too, along with the Eurasians, progressively sank their roots in Singapore and a Singapore identity was developed.

Today, the rising number of inter-ethnic and transnational marriages has also added to the complexity of Singapore’s social mix. In 2018, 22.4% of total marriages were between grooms and brides of different ethnic groups, a 16.7% increase from 2008. Singaporeans are more distinct and diverse than ever before.

However, the entry of newcomers to Singapore, coupled with stresses of today has led to increased xenophobia as many view them as competition. Technological and trade disruptions have fueled concerns about workplace competition and security, with some questioning the need for newcomers with whom they have to compete for jobs. Greater connectivity and social media have also made it easier for divisive narratives to take root.

But as a small and open economy with an ageing population, increasing numbers of trans-national families, and low Total Fertility Rate , Singapore has to keep its doors open to achieve further growth.

Singapore’s approach to new citizens is one of integration, not assimilation, to welcome and not take away, as we have done from our start as a migrant nation. As PM Lee noted, at the official opening of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre on 19 May 2019, being Singaporean, he said, has “never been a matter of subtraction, but of addition; not of becoming less, but more; not of limitation and contraction, but of openness and expansion”.

To integrate new citizens, Singapore needs to reaffirm and promote shared values, find and grow common spaces, share collective experiences and strengthen emotional bonds among our people. Opportunities for citizens and new ones to interact and understand one another better continue to be key.

To support the social mixing and integration of newcomers, the National Integration Council (NIC) promotes a “whole-of-society” approach for integration , by working with its tripartite members and partners from the community, schools, employers and the Government to develop programmes and initiatives.

For example, naturalised citizens granted in-principle approval for Singapore citizenship must complete the Singapore Citizenship Journey programme. In addition, community groups such as the Integration and Naturalisation Champions help naturalised citizens and permanent residents settle into their neighbourhoods. These initiatives help newcomers’ understanding and appreciation of Singapore’s history and development, norms and values, and also to build stronger ties with the local community to better understand Singapore’s identity, culture, and people.

In the end, integration in practice means everyone plays an important part in helping newcomers settle and adapt to Singapore’s way of life: neighbours can start a friendly conversation about anything from the humid weather to the beautiful Angsana trees; students can share folklore about the Merlion or the Red Hill swordfish; colleagues can bond over kaya toast in the kopitiam, and families shopping at a supermarket can share tips about where to buy the freshest durians.

It is in the mundane, daily interactions with locals that immigrants will naturally find their new, uniquely Singaporean comfort zones.

With the influx of new immigrants and more mixed marriages across race and nationality, some Singaporeans are grappling with even more existential questions, such as whether our ethnic labels and CMIO (“Chinese, Malay, Indian, Others”) categorisation are still relevant. Many also debate what social harmony, multicultural integration and racial balance should look like in today’s society, where numerous marked differences exist even within each “race” – for example, Chinese immigrants from different provinces can have vastly different cultural backgrounds, not to mention their differences compared to Singaporean Chinese.

There are no easy answers to such questions. Nor are they definitive – indeed, they are not meant to be, with Singapore’s diverse and multicultural population and multitude of viewpoints, as well as the younger generation’s propensity towards open dialogue and acceptance of differences. They are also engaging more actively in dialogue about our national identity through new social media platforms.

While Singapore’s social mix is increasingly varied, many Singaporeans, including new citizens, share a common sense of pride in Singapore’s strengths. National pride can be linked to a stronger sense of identification with one’s country. Positive sentiment about the country’s strengths can help to reinforce our citizens’ sense of ownership and loyalty, thus strengthening national identity.

Many Singaporeans share a strong sense of satisfaction with the country’s multiracial harmony, food, excellent healthcare system and cleanliness. These were named as the top five sources of national pride among 24 components identified by an IPS study released in 2021 . The IPS list also included the Singapore Armed Forces, the education system and the Government’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As Singapore continues to grow its economy and improve the workforce with an appropriate influx of foreign talent, Singaporeans will need to embrace greater diversity in our society.

We are already witnessing many nationalities and races in our country’s demographic makeup, as more immigrants and foreign residents have come here to work over the past few decades. Many foreigners marry local Singaporeans and decide to make Singapore their new permanent home. One in four marriages in Singapore is between a local and a non-Singaporean. This, in turn, is making our Singapore identity even more multi-faceted.

Building a shared identity with a new social mix

With increasing diversity among our population, future generations of Singaporeans will likely be more multicultural. Some may not fit easily into ethnic labels and CMIO (“Chinese, Malay, Indian, Others”) categorisation because they come from mixed marriages and immigrant backgrounds or have spent many years growing up or working abroad. They may not share the same institutional memory imbued through the Singapore school system and national education lessons. However, they can still integrate into Singapore society by being immersed in our local communities and exposed to our national values.

A 2020 study by the Institute of Policy Studies showed that most Singaporeans believed that it was good having different cultures and nationalities in the same neighbourhood. But nearly six in 10 polled said that many immigrants were not doing enough to integrate into Singapore.

While there are specific government programmes to help new immigrants integrate into the Singapore society (refer to Part 4 “Integrating New Citizens” MCCY - Citizens’ workgroup for Singapore Citizenship Journey), it is also important to build a shared identity through everyday interactions and conversations with locals of all backgrounds.

Indeed, creating a common identity calls for everyone in the social mix – whether they are born in Singapore or naturalised citizens – to embark on collective learning journeys to internalise Singapore’s national values.

The fact is, Singapore’s identity is not static or immutable: each successive generation of Singaporeans can contribute to forging a shared national identity that transcends all lines – be it cultural, racial, religious, or economic. Some ways to strengthen our Singaporean identity are through food, arts and sports, which are universally accessible to all regardless of background and constantly evolving to accommodate new participants and ideas.

They can also participate in more broad-based and inclusive dialogue, as described in the next section on Singapore’s shift towards a more collaborative approach to articulating our national identity and values.