Singlish and our National Identity

Singlish and our National Identity

While many today consider Singlish part of our national identity, this has not always been the case! Let us take a moment to explore Singapore’s complex relationship with English/Singlish over the years.

The History of English in Singapore

English was first introduced to Southeast Asia when the British colonial settlers arrived in region in the late 1700s, and eventually arrived on Singapore’s shores in 1819. However, Malay remained the lingua franca even up until the beginning of the 1900s.

In the early 1900s, institutes of higher learning that taught in English were established. Consequently, proficiency in English became key to social mobility in terms of further education and employment opportunities. By extension, English took on greater and greater importance, such that at the end of British colonial rule, English had become a language of prestige and was often used as a lingua franca between different ethnic groups. This more widespread use of English led to the birth of a colloquial variant used in informal domains, influenced by the different languages and dialects spoken – also known as Singlish.

In 1960, a year after the People’s Action Party (PAP) came into power, it implemented a bilingualism policy that made learning English mandatory in primary schools. This was followed by secondary schools in 1966. English was established as the official lingua franca in post-independence Singapore, due its ethnic neutrality, as well as the economic benefits it allowed in terms of international trade and access to English-language educational resources.

The War Against Singlish – The Speak Good English Movement

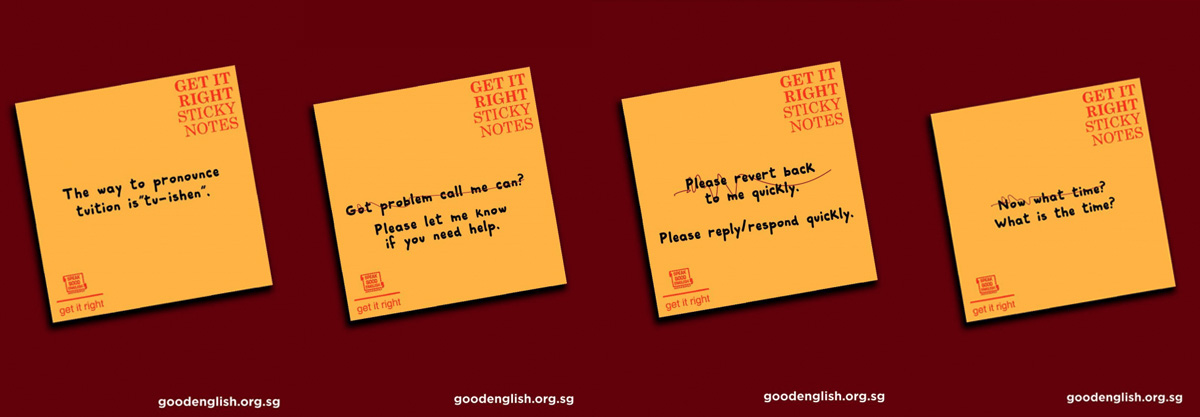

However, this shift entailed some sacrifices. Over the next few decades, Singaporeans struggled with both bilingualism, and with speaking good English. The problem came to a head when a report emerged in The Straits Times in 1999 about declining English standards in Singapore, which some attributed to the pervasive use of Singlish. This provided the impetus for the launch of the Speak Good English Movement (SGEM) in April 2000, which emphasised the speaking of grammatically-correct, internationally-understood English. The war on Singlish had begun.

However, from the onset, the SGEM has not been without its challenges. Those who argued against Singlish usually emphasised the pragmatic benefits speaking standard English brought, in terms of social mobility and personal gain. However, this overlooks the fact that the prevalence of Singlish in Singapore society also carries with it its inherent value, as a means of communicating authenticity and building solidarity, although this finding seems to depend on gender and education levels.

Furthermore, with more Singaporeans going abroad and more foreigners living in Singapore, Singlish has become a type of transferrable skill, or a cultural commodity, that non-Singaporeans pick up and value. In fact, a 2015 article in the BBC showcased numerous examples of non-Singaporeans speaking and showing appreciation of Singlish. Recently, films produced in Singlish have even managed to win awards at film festivals around the world, contradicting earlier claims by the government that Singlish lacks economic value, and is a hindrance to communication on an international stage.

Another common argument is that Singlish hinders one’s ability to learn and speak standard English, which is a crucial skill in this globalised world. However, some academics have questioned this assumption, arguing that Singlish is a natural manifestation in response to globalisation, that complements the presence and use of English in Singapore. Therefore, eradicating Singlish will not necessarily bring about an improvement in the level of standard English in Singapore, just as the elimination of a local culture might not necessarily lead to the embrace of a global one. Instead, Singaporeans should be exposed to and taught to value both Singlish and standard English, learning to use them in different contexts and to code-switch smoothly between them.

Validation of Singlish – Speak Good Singlish Movement and Dictionary endorsements

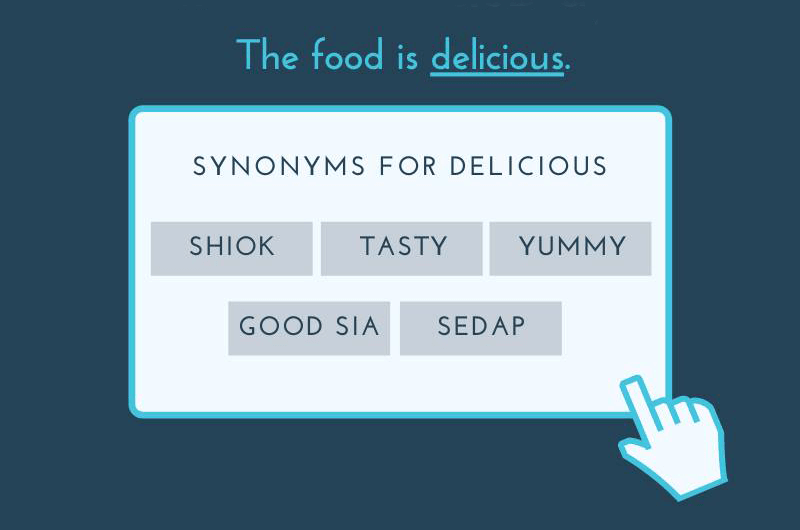

In response to the SGEM, a Speak Good Singlish Movement (SGSM) was launched anonymously in September 2010, to celebrate the use of Singlish, and to distinguish “proper” Singlish from plain broken English. This display of linguistic chutzpah, or confidence, shows the development of Singlish and its rejection of any anxiety about the use of Singlish, especially as a result of the SGEM. In 2016, Singlish speakers received even more reason for their confidence, when the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) added 19 new “Singapore English” items to its lexicon, making it a grand total of 27 Singlish words in the prestigious dictionary.

This development cemented the central position Singlish occupied for the younger generation, with about half of the respondents of a recent survey claiming that Singlish is a part of Singapore’s national identity and culture.

Singlish as common identity

Despite these glowing endorsements, Singlish is far from established as part of our national identity. In a 2018 study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), only 8 per cent of respondents chose Singlish as the language they identified with the most, compared to one-third identifying with English, and 2 per cent with their official Mother Tongue languages. Some Singaporeans have also begun to use Singlish as a test of Singaporean-ness, resulting in Singlish becoming a discriminating force and gatekeeping mechanism, rather than source of solidarity. Those who were unable to speak Singlish “properly” are labelled ‘fake’ Singaporeans, in a manner reminiscent of how English-educated Chinese are mocked for being “bananas”.

Although Singlish still lacks acknowledgment as part of Singapore’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, its pervasiveness and status amongst Singaporeans cannot be ignored. As the world starts to take notice of our home-grown dialect, maybe it is time for Singaporeans too to start thinking about protecting and preserving Singlish as something valuable to our culture and identity.