Special Assistance Plan Schools

Special Assistance Plan Schools

In recent conversations on racial harmony in Singapore, the Special Assistance Plan (SAP) has repeatedly come up as an example of racial inequality in our education system.

Dominant narratives in the media today tend to cast the SAP as examples of ‘Chinese privilege’, ‘Chinese elitism’ or even ‘Singapore’s own bumiputera policy’ while overlooking the precise reasons for their founding.

More nuanced discussions tend to include some mention of the historical reasons, but often fail to consider the underlying considerations or the presence of real alternatives. While engaging in civil discourse is important, especially for our young people, we should not allow narratives that do not reflect the full picture to take center-stage in the conversation. Let us take a look back at the history of the SAP, to understand how it came about and why it still exists today, and how its intention is not to provide benefits to any one particular race.

The History of the SAP

In the 1960s to 1970s, as English gained greater importance as the lingua franca in Singapore, parents began to send students to English-stream schools instead of vernacular schools. This led to the closing of many vernacular schools, and the proposed merger of Chinese-medium Nanyang University and English-medium University of Singapore, which was completed in 1980.

This decline led to the concern over preserving the best Chinese-medium schools in Singapore, especially those with rich histories dating from the early 1900s. Then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew believed in the value of preserving these schools, because he believed the traditional Chinese values taught through the Chinese language would help strengthen Singapore society. Therefore, the SAP was implemented in 1978, to develop nine Chinese-medium secondary schools into bilingual institutions with comparable standards of English to other schools. In the next 15 years, as most of the Chinese-medium primary schools closed down due to declining enrolment, MOE extended the SAP to 10 primary schools, followed by another five later on.

The excellent performance of the first batch of SAP school students in the O-level examinations contributed to a significant increase in the number of applications for SAP schools. Thanks to the SAP, schools like Nanyang Girls’ High School and Hwa Chong Institution, which were involved in historical moments during World War II when they were used by allied defenders, were preserved.

(Image: Wikimedia)

(Image: Wikimedia)

Related programmes and campaigns

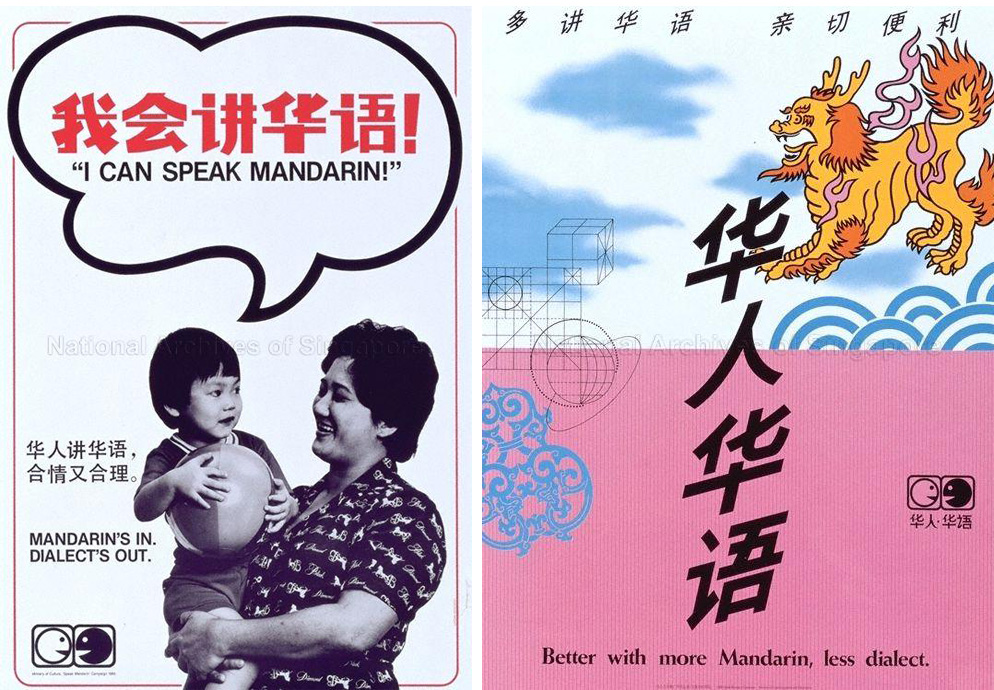

Along with the SAP, the government also introduced the Speak Mandarin Campaign from 1979, to encourage Chinese in Singapore to learn and speak Mandarin instead of their dialects. The standardisation of Chinese as the vernacular was intended to reduce the language barriers between the different dialect-speaking Chinese groups, and facilitate communication with Mainland Chinese. However, forcing these dialect-speaking Chinese to learn Mandarin in schools along with English essentially made them learn two second languages. This “sacrifice” of Chinese dialects in schools, accompanied by the elimination of dialect programmes from local media, led to the near-elimination of dialect-speaking ability within one generation. This loss of our cultural-linguistic heritage is a key example of the trade-offs our founding fathers had to make to secure our economic future.

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

(Image: National Archives of Singapore)

In 2005, with the strengthening of the Chinese economy, the Bicultural Studies Programme (BSP) was established in three SAP schools to develop among students a strong understanding of China’s history, culture and contemporary developments, in addition to a good command of the Chinese language. In 2007, a review taskforce chaired by the then-Minister of State Gan Kim Yong encouraged SAP schools to develop their own flagship programmes related to the learning of the Chinese language, culture and traditions. This led to the introduction of examinable and non-examinable subjects in the different SAP schools centred on Chinese.

Discussion – Is the SAP still useful today?

These policies were originally meant “to preserve traditional Chinese values and nurture bilingualism”, to facilitate business with China and allow Singapore to benefit from China’s economic rise. While this is important in the context of a fast-growing China, which is Singapore’s largest trading partner, Malay and Tamil learning should be enhanced as well, with Indonesia, Malaysia, and India also offering tremendous opportunities. Former Education Minister Ong Ye Kung said in 2019 that many young Singaporeans are less conscious of their ethnic identity, and there are more specialised programmes to promote Mother Tongue learning such as the Language Elective Programmes for Chinese, Malay, and Tamil.

If we choose to retain the SAP, the problem of racial segregation needs to be addressed. Since its inception in 1979, concerns have been raised about the lack of opportunities for students in SAP schools for interracial mixing. In response, some SAP schools have made Malay a compulsory subject for lower secondary students, while others introduced opportunities for students to broaden their social interactions through community-based activities or exchanges with cultural groups and other schools. Although these measures were deemed sufficient in 1990, it is worth re-examining them in light of the recent anecdotal reports of students experiencing casual or outright racism at the hands of those from SAP schools.

Conclusion

In our small multilingual society which open to the world, it is inevitable that society gravitates towards a common language, in this case the international lingua franca of English. To preserve our economic advantage in doing business with China and the cultural-linguistic heritage of each race-community, however, we need to find a balance between emphasising the learning of Mother Tongue languages, showing fairness and equality to all races, and preserving the high level of English we have. We should also work to dispel myths of systemic racial discrimination, to preserve the racial harmony we enjoy.