Public Transport Network

Public Transport Network

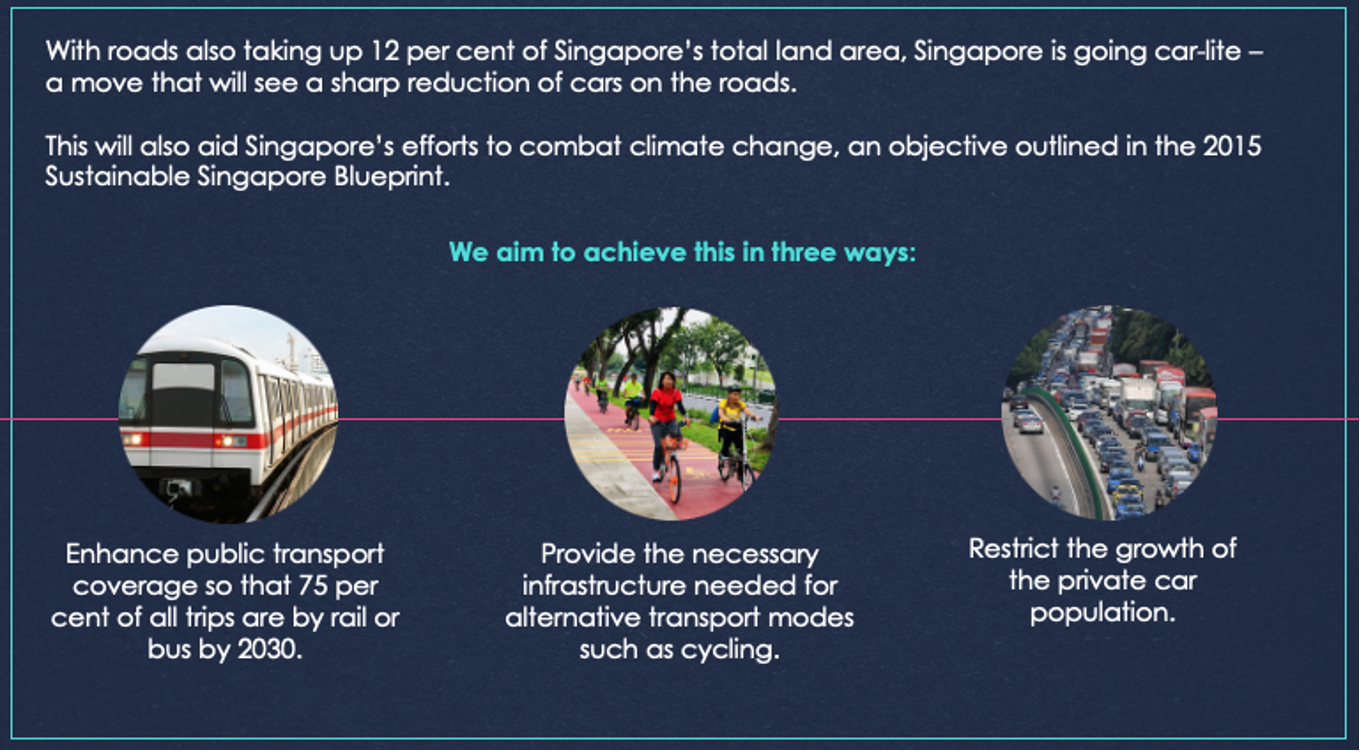

As the most space-efficient way that allows large numbers of people to travel, Singapore’s public transport network has been crucial in helping us manage our limited land space.

Image: Ministry of Transport

Image: Ministry of Transport

Beginning from the 1950s, buses were the primary mode of public transport. However, in 1967, the State and City Planning Project, which had been initiated that same year, proposed building a rail system to develop Singapore’s public transport system. This rail proposal was later incorporated into the 1971 Concept Plan to serve a rapidly growing population and ease traffic congestion problems.

Great Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Debate of the project.

Expected to cost S$5 billion, it was to be the most expensive public project undertaken by Singapore at that time. The ‘Great MRT Debate’ ensued, with founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and then-Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee on opposing sides. While the PM Lee supported the MRT plan as it would bolster economic and social growth, Dr Goh was unsure if the high costs would make it a worthy investment.

Instead, Dr Goh advocated for a cheaper all-bus system. However, the 1982 Comprehensive Traffic Study later deemed that Singapore’s limited land could not cater for the amount of road space that an all-bus system required.

Eventually, after nine studies that spanned a decade, Singapore decided to build the MRT, which first opened in 1987.

Image: One of the first trains delivered to Singapore / MITA from NAS

The new public transport system enabled the government to decentralise urban centres. With a robust public transport system, residential areas could be moved farther away from the city centre, freeing up space in the central business district (CBD). a process of ‘decentralisation’ – of moving freeing up space in the central business district (CBD) – as residential areas could be built around the stations. Businesses and industries could also be moved outside of the CBD to create pockets of residential and commercial activity in the heartlands.

This was the case in Toa Payoh. When the town was being constructed in the early 1970s, a plot of land was set aside for the future construction of the MRT. Light industries set up shop alongside residential estates, which created jobs in the heartlands and prevented the transport system from being overloaded.

Image: LTA

Image: LTA

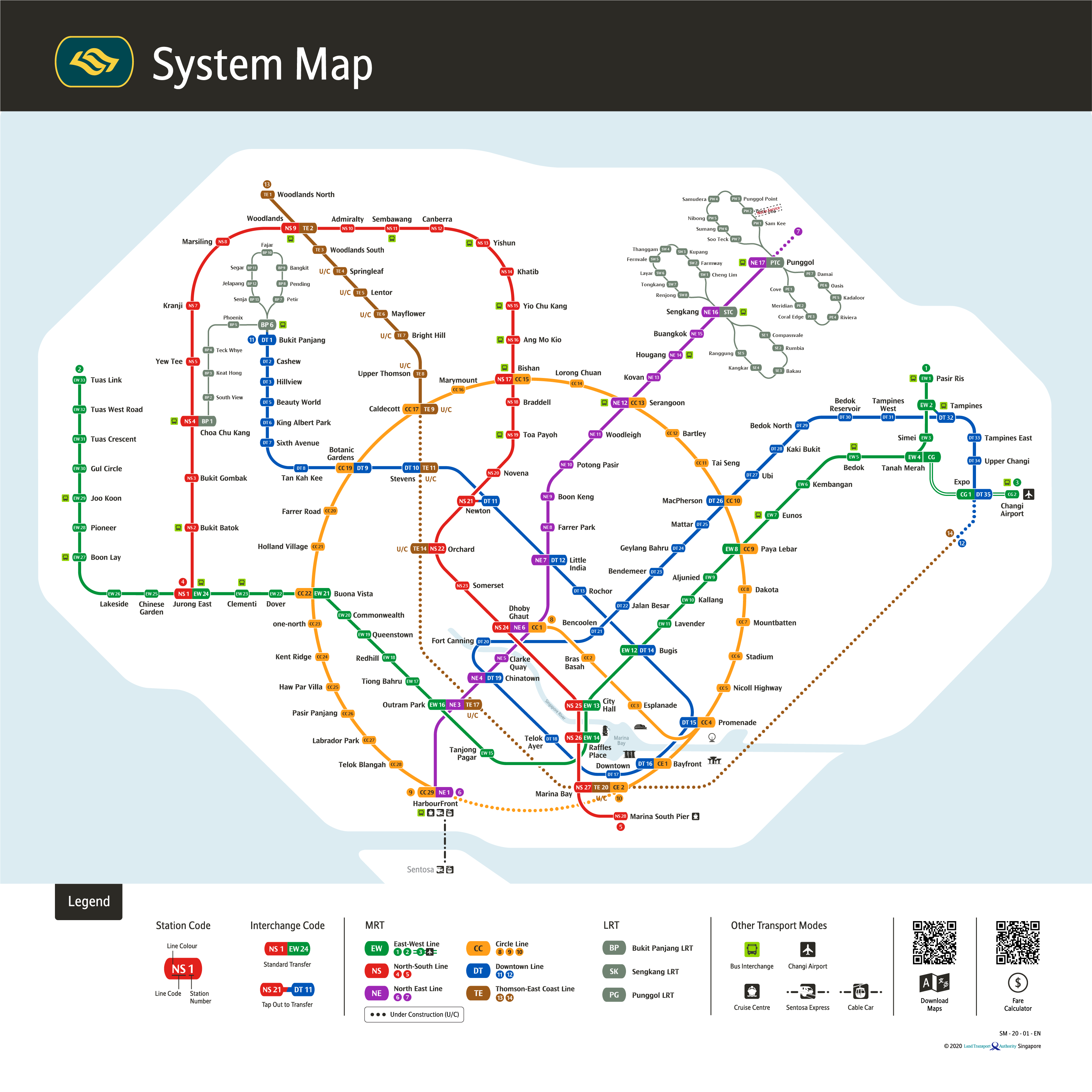

Today, the MRT system is the backbone of Singapore’s public transport system. Singapore has six MRT lines consisting more of than 130 stations, with about 200km of rail spanning the island. It is complemented by the bus system, which provides connections between residential towns and MRT stations. The MRT and bus systems are brought together by the Integrated Transport Hubs (ITHs) – bus interchanges linked to MRT stations and commercial developments such as shopping malls. There are currently nine ITHs in Singapore.

The Government has also committed to building more MRT lines to alleviate the load on existing lines. The Land Transport Authority’s (LTA) Land Transport Master Plan (LTMP) 2013 included plans to further improve Singapore’s rail connectivity to reach more housing and industrial areas, with an eventual aim to have eight in 10 households live near an MRT station by 2030.

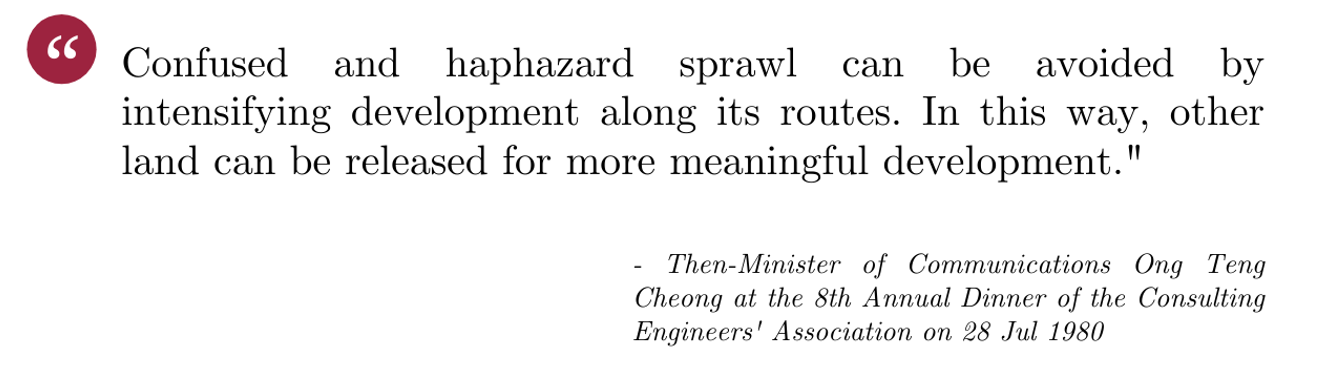

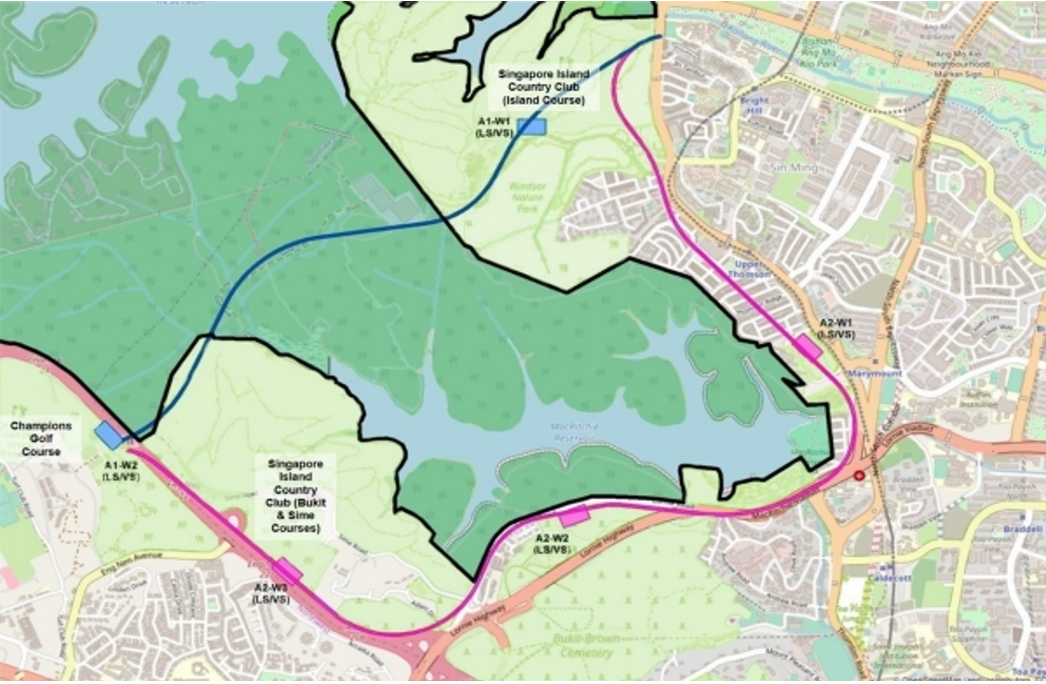

However, expanding the MRT network no doubt involves trade-offs. For instance, there were environmental concerns over constructing the future Cross Island Line, as it would cut through the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, as seen below, and cause environmental harm.

Image: Cross Island Line / LTA

Image: Cross Island Line / LTA

In response, LTA spent six years engaging in discussions with various interest groups. It spoke to residents in the affected Thomson area worried about losing their homes, and had discussions with nature groups.

Eventually, after all the feedback, LTA adapted the plan. It decided not to cut through the Thomson residential area, opting instead to build the new line directly underneath the nature reserve. Moreover, to minimise environmental damage, LTA said that it would tunnel 70m below the surface (instead of the usual 20m to 30m for other MRT tunnels), even though this would cost at least S$20 million more. It also reduced the number of boreholes drilled in the reserve from 72 to 16 to mitigate the environmental impact of the required soil tests.

Another impetus to building our public transport infrastructure is to reduce our reliance on cars. It will allow us to remain connected, while lowering the impact that our mobility has on limited land space and resources.